Bird’s Nest, part of Chinese culture and tradition for hundreds of years, is prized by aficionados for its rarity and nutritional and medicinal properties.

Yan wo, or bird’s nest, is sometimes referred to as ‘the Caviar of the East’. The history of bird’s nest consumption can be traced back to China nearly 1,500 years ago during the Tang Dynasty period (A.D. 618-907). It was believed that birds’ nests had been brought back from ‘Nan yang’ (the southern countries), by sea-faring Chinese sailors, and introduced to the courts of China’s Emperor as a supreme delicacy. During that era, only the family of the Emperor and his court officials had the privilege of consuming the highly priced bird’s nest. It was only at the end of the Emperor’s rule that the rest of the population were introduced to bird’s nests, and their value, and the demand for them, has continued to increase due to their rarity and nutritional properties.

Edible birds’ nests are exclusively built by small birds known as swiflets which belong to the large family of the common swallow, but only the nests from three species are edible. The nests are built from the bird’s salivary secretion which is abundant, particularly during breeding season. The saliva has a unique chemical texture which is used to make the nests. These nests, often found clinging to the ceilings of caves as high as two hundred feet, are built by both parents expressly for raising their young. When the hatchlings are ready to fly off, the nests, found in many coastal caves of South East Asia including Borneo, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, are then abandoned. The costly edible nests are known as red blood nests because it was thought that the red was blood stains from the birds, however, it is a ferrous material (iron) from the chemical interactions of various natural factors such as temperature, humidity and the contents of the cave walls.

To harvest the edible birds’ nests requires the use of highly trained collectors, sometimes known as ‘Spidermen’ who have generally inherited their jobs and learned the skills from their fathers. Harvesting is done in several ways, depending on the cave’s location, ground elevation, and other geographic considerations. In caves where the ceilings are low, bird’s nests are gathered by hand. In taller caves, bamboo scaffolds and wooden walkways are built so that harvesters can reach the nests. Some swiflets have found the eaves of abandoned coastal houses favourable for building their nests so houses have been commercially constructed especially for the swiftlet to make their nests.

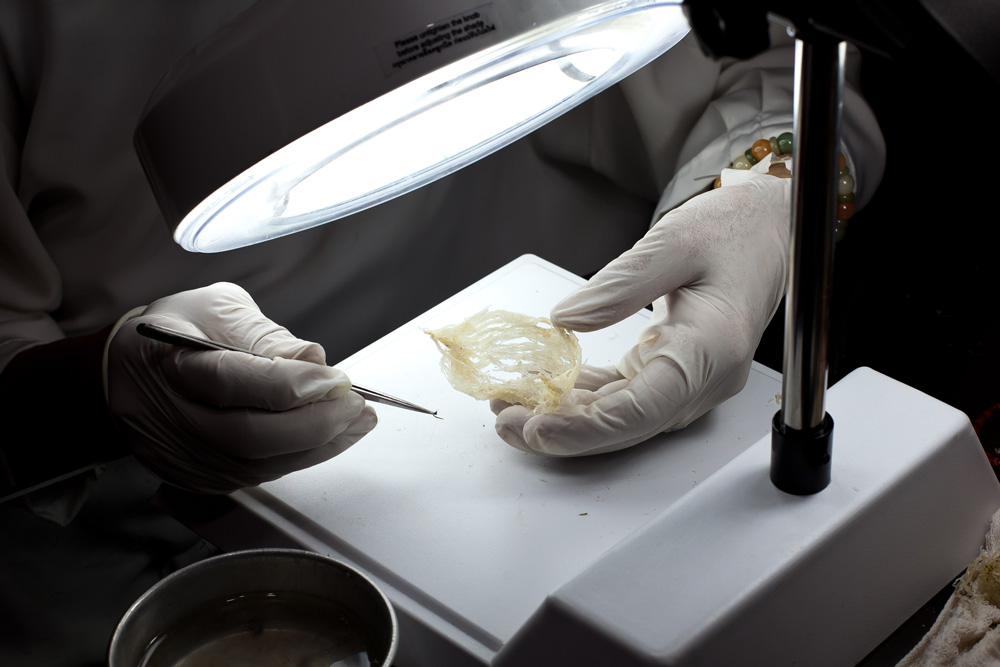

Processing is minimal for whole nests with few feathers if they are white and relatively clean. Nests with lots of feathers, known as black nests, need extensive processing. This is a long, tedious, and labour-intensive task. The black nests have to be washed and soakedwith warm water for up to forty-eight hours. Hot water can cause nests to expand and their strands to unravel, then tweezers are used to pluck the feathers and other foreign particles from the wet nests. Workers are trained to pick out only impurities and not destroy or remove actual nest strands, then hard corners of the nests are trimmed and removed. Once the nests are completely cleaned and trimmed, their long strands are put into cup-shaped metal moulds. This helps them retain their original shape after which they are airdried, graded and packed for shipping. Each piece of processed, dried, raw bird’s nest usually weighs about three and a half to four grams.

The preparation of raw birds’ nests can be done in two ways. Premium white whole nests are made to look like a halved cup by putting them in to a wire frame to shape them. The more affordable black nests are dried and moulded into flat leaf-like pieces.

To prepare them, the nest is rinsed quickly and then soaked in warm water to allow it to expand. Then it is either steamed or double-boiled for at least two hours. There are many recipes that use birds’ nests, the most common is in soup, typically with lean chicken. They can also be prepared as a dessert by adding rock sugar, or pitted dried red dates, lotus seeds, even white fungus, some chefs add coconut milk with fruit such as papaya, mango, or pear. Birds’ nests can be pre-prepared and bottled for convenient culinary usage.

The health value of bird’s nest was noted by Chinese doctors at least three hundred years ago and since then has been used in traditional Chinese Medicine. As well as using the nests the Chinese believe eating the swiflets’ lungs, stomach, and kidneys improves the appetite and complexion. They are thought to aid recuperation from debilitating illnesses because of their easily digestible glycoprotein and other nutrients. The soup, a mostly clear gelatine, is served in small jars, which is now very popular throughout Asia, perhaps because it has the reputation of being an aphrodisiac or having traditional health enhancing qualities. Based on recent research, it appears thatthis claim of health benefits is not a myth but based on real fact. According to a recent medical research reported by Hong Kong Chinese University, the cell division enzyme and hormone of bird’s nest can promote reproduction and regeneration of human cells. It also helps promote one’s immune system and enhances body metabolism. For centuries, Chinese royal women consumed bird’s nest to enhance their beauty. Their ingestion was believed to improve their skin and complexion.

Sustainability of the birds’ nests is an important consideration and to protect the swiflets and their habitat, most countries where bird’s nests are harvested, have laws about collection practices. Sarawak, for example, only allows black nests to be harvested at seventy-five day intervals. In Vietnam, collection is allowed twice a year. As a result of these and other regulations, the quality of the nests in these places are superior. In recent years, more commercial swiflet houses have been built for what is called ‘ranching’. These buildings mimic natural cave environments with optimum humidity, light and noise levels carefully maintained and monitored.

Workers are trained to manage these homes to avoid harm to the birds by pests and predators. Edible bird’s nests are among the most expensive Chinese delicacies and tonics consumed by man. High quality, clean white nests which come from Sabah, Thailand and Vietnam can retail at well over two thousand dollars a pound. Along with shark’s fin, dried abalone and premium sea cucumber, bird’s nests are frequently on the menu at exclusive banquets. They reflect the status of the host. Today, while the price has not come down, modern technology in processing and marketing means bottled bird’s nests are becoming easily accessible.

These bottled bird’s nests come in a variety of flavours, some without sugar, some with added herbs or nutrients including ginseng. One popular way is to add some bird’s nest to congee or soup.

The primary target for birds’ nests is the Chinese community around the world, with Hong Kong, Mainland China and Taiwan the top consumers followed by Singapore, U.S, Middle East countries and others. Bird’s nest soup is considered an esteemed cuisine by upper class Chinese families and so appreciated for its health benefits that diners at a certain Hong Kong restaurant are willing to pay almost US$60.00 per bowl for the highest quality bird’s nest soup. Although there is a stable demand from restaurant consumers, the peak season of demand comes during the Chinese New Year period.

Gift giving of bird’s nest is especially popular during this period as it wishes the recipient good health and longevity of life as well as symbolising the givers affluence and status in society. Bird’s Nest Soup has been a part of Chinese culture and tradition for hundreds of years.